Figures In The Landscape

Standing Inside the Landscape – Figures Lead The Way

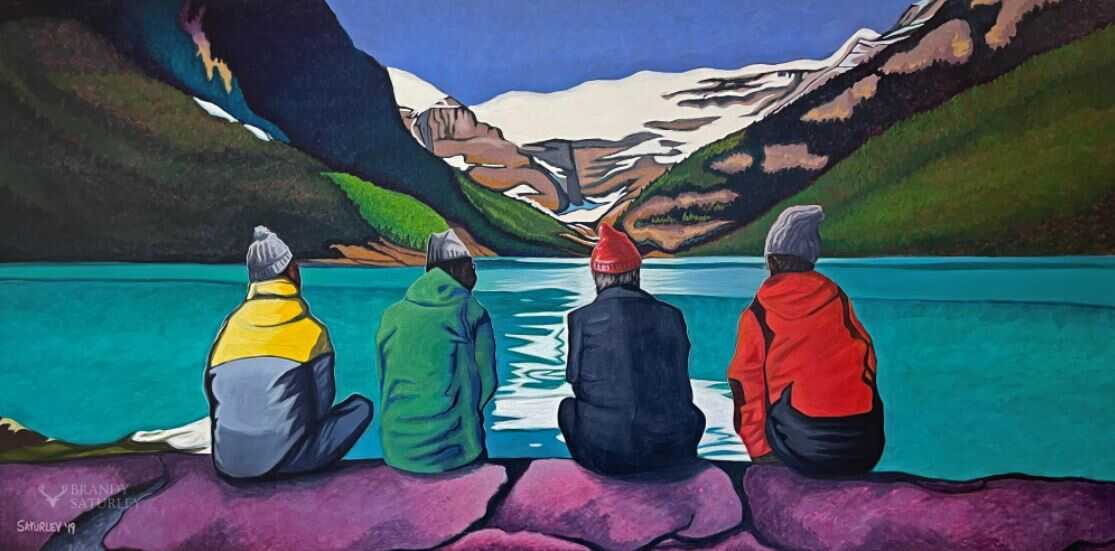

In many of my paintings, the figure is not meant to be a portrait. It is a presence. Often shown from behind or slightly turned away, the figure stands quietly within the landscape, facing something larger than themselves. I’m less interested in who they are than in where they are, and what it feels like to pause there.

This way of working connects to the art historical idea of the Rückenfigur, a figure seen from behind that invites the viewer into the scene rather than confronting them. In art historical research, it is debated whether the Rückenfigur actually invites identification or rather encourages second-order observation. In my own work, I use this perspective to create an entry point. By turning the figure away, I’m inviting the viewer to step into the painting and share the moment, to stand where the figure stands and look outward.

The clothing and gestures are familiar. Winter hats, red in everyday clothing, the subjects hair. These details ground the work in everyday life and help dissolve individuality. The figure could be anyone. They could be you. By withholding facial expression, I leave space for the viewer to project their own thoughts, memories, and experiences into the scene.

The landscape is never a backdrop for me. It is an active presence. Canada’s geography, weather, and vastness shape how we move through the world, and I try to reflect that lived experience in my paintings. The figures don’t dominate the land or pose within it. They stand in relation to it, sometimes dwarfed by scale, sometimes absorbed into it, always responding to place.

Much of this work grows out of my travels across Canada and my desire to create in direct response to where I am. I’m drawn to moments of transition. Standing at the edge of a frozen lake, pausing along a highway, looking out across a mountain range. These are in-between moments, when movement slows and awareness sharpens. Painting them becomes a way of marking experience.

By positioning the viewer just behind the figure, I shift the role of looking. Rather than observing from a distance, the viewer is invited to stand beside the subject, facing the same horizon. The painting becomes less about observation and more about presence. A shared vantage point.

Ultimately, these contemplative figures reflect how I experience place myself. I don’t arrive with answers. I arrive with attention. The act of standing still, looking outward, and listening to the landscape is where the work begins.

Figures In The Landscape – Rückenfigur in the studio

The idea of the Rückenfigur doesn’t only appear in my finished paintings. It has quietly become part of my studio practice as well. At the end of nearly every painting, I take a moment to sit with the work. I place my orange velour retro chair a short distance from the canvas and sit facing it, allowing the painting to look back at me.

The orange chair of contemplation – Brandy Saturley – 2025

From behind, the view is simple. The back of my head, my shoulders, and the painting beyond, partially obscured. In that moment, I become the figure within the scene. The act of contemplation is no longer painted. It is lived. By photographing this final pause, I’m capturing the closing breath of the painting, the moment just before it leaves the studio.

This ritual mirrors the same perspective I return to on the canvas. A figure seen from behind. A shared vantage point. My presence interrupts the view, but it doesn’t dominate it. The painting remains ahead of me, just out of full view, asking for patience and attention rather than immediacy.

These images mark the transition from making to letting go. Sitting there, I’m no longer adding or correcting. I’m listening. The painting has said what it needs to say, and my role shifts from creator to witness. The Rückenfigur becomes a way of acknowledging that shift, a quiet handoff between artist, artwork, and viewer.

In obscuring the painting slightly, the photograph does what the paintings themselves do. It resists full access. It slows the moment. It asks the viewer to imagine what lies just beyond the figure, and to step into that space of contemplation themselves.